A good friend, who is an analytical chemist, just read Andy Weir’s debut novel The Martian—and raves about the compelling story, meticulous detail, and accuracy. Without these fundamental elements of quality science fiction, he would have quit reading upon encountering a flaw. Now he’s pumped to catch the movie.

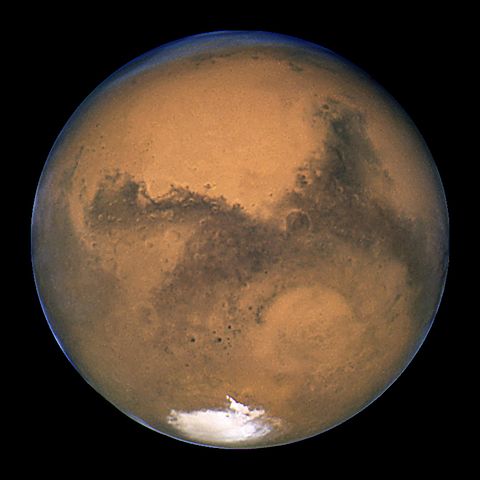

Here’s a one-sentence summary (in case you live on another planet and missed the cinema hoopla): an astronaut, stranded on Mars for more than four years, can survive only by relying on science and ingenuity. As Meghna Sachdev notes in Science magazine, “The story’s real heartthrob is, well, science. Between the technologies showcased on the Mars mission and its breathtaking Hermes spacecraft, the astronaut’s ingenious solutions for staying alive on a deserted planet, and the creativity of scientists back on Earth, the story reads like a love letter to science—and a surprisingly plausible one at that.”

Sachdev delivers an eye-opening interview with the brains behind this box-office phenomenon: Andy Weir, director Ridley Scott, and Jim Green, NASA’s director of planetary science and an adviser on the film. Science geeks are in fashion. Nitpicking realism (e.g., space suits, the Mars Ascent Vehicle, habitats, physics) renders movie magic, even plot points. (Caroline Framke, Vox‘s Culture columnist, nicely amplifies five scientific twists in The Martian.)

It’s refreshing to hear science is cool—for the moment—to the general public. I grew up in the decade of the intense space race. Eight years after President John F. Kennedy challenged Americans’ spirit of adventure, two US astronauts walked on the Moon. An estimated 600 million TV viewers—including every kid and parent in my small world—watched the lunar landing on July 20, 1969.

The Pew Research Center recently released the report “A Look at What the Public Knows and Does Not Know about Science,” which features an interactive quiz. It points out that the developments in science and technology raise issues for public debate (e.g., space exploration, climate change, genetically modified crops). Nonetheless, another 2015 Pew Research report says that 84 percent of members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science view US K–12 education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as “average” or “below average” when compared to that of other industrialized countries.

Science often becomes a political football. However, it is not a Republican or Democratic issue. Rather, it is an essential ingredient in our education and evolution as a society. It’s on us to dig into information so we can listen to a range of views from the perspectives of government, business, academia, and research. The media do not always present information following strict standards of science journalism. It’s on us to demand better. As Steven G. Mehta observed earlier this year in Business Insider, “But in fact, science is messy. It starts with a hypothesis, a theory about the way something works. One scientist finds evidence that seems to prove or disprove that idea. Others pile on, testing it, modifying it, and sometimes disproving it.”

My parents did not pursue careers as scientists, but their education was grounded in the sciences. Mom studied botany, and Dad focused on a pre-med curriculum. They were comfortable with the facts of science and their leap of faith in God. Yes, they graduated in the old-school period—1949. Nevertheless, I cannot fathom their acceptance of politicians who sidestep a science-related policy question by answering, “I’m not a scientist,” with the implication “therefore, I do not need to answer.”

In the late summer of 1969—under a starry, starry sky far from city lights—my dad and I lay on the floating dock just steps from our lake house. With our backs against the warm, graying boards, the rock of the current and the squeak of Styrofoam floats lulled as we gazed upward at our tiny patch of a nearly 14-billion-year-old universe.

“Not many miracles get bigger than that,” Dad said, sweeping his hand against the vast night. Then he fell silent to the water’s gentle lap.

Leave a Reply